In the italian village of Sirolo (in the Marche region) each May 9 is celebrated the Palio of St. Nicholas, patron of the town, divided into two chanllenges inspired by the life of the saint. Between the two challenges, that of the Contrade and that of the Canaja, it is curious to note that one of them has taken originally from a “bad” translation of a legend about the saint handed down over the centuries.

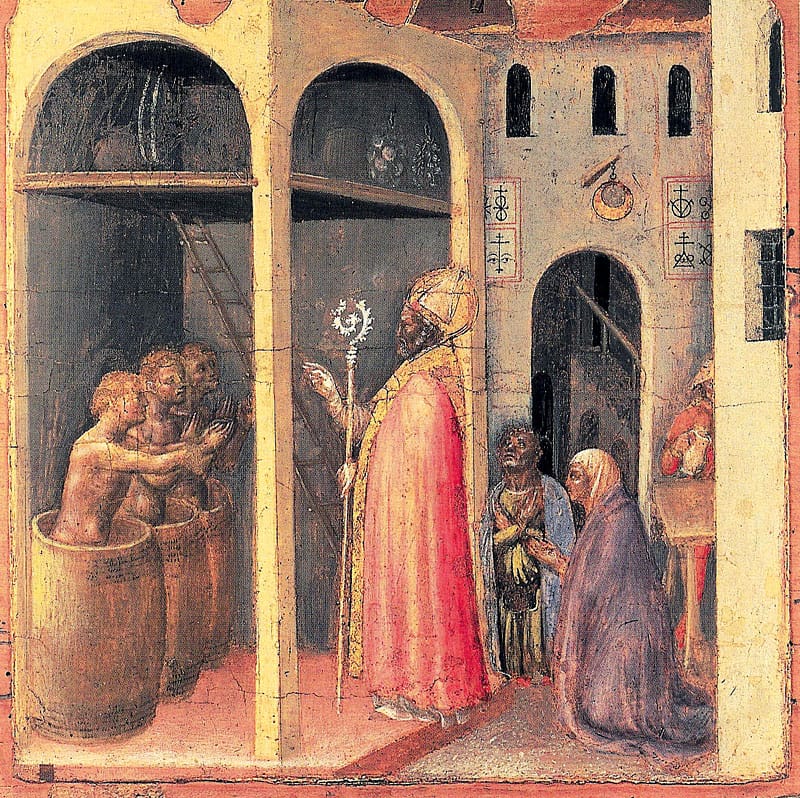

We are talking about the “Disfida della Canaja”, challenge that sees children aged 11 to 13, compete in a race to “recompose” children’s puppets that the legend sees killed and cut into pieces by an innkeeper. But let’s go step by step. This legend, that of the “Three children and the innkeeper,” tells when the Saint, going to the council of Nicea, stopped at a tavern, and the innkeeper served him a dish that instead of being fish-based was of human flesh. The Saint, divinely inspired, asked the innkeeper to examine how the fish was kept and the innkeeper showed him two barrels containing salted meat. Nicola, standing in prayer, made the miracle of reconstructing and bringing to life three children whom the innkeeper had killed before and who, by denying the evidence, wanted to dispose as fish to his customers. The innkeeper, having seen the miracle, was pushed to conversion.

It is not a rare occurrence that over the centuries the stories handed down take different nuances, each people has reworked them according to their culture or sensibility, it is normal that names, places, and characters have changed. It is enough that between two languages a word is interpreted differently that a story can change completely.

Indeed, the story that we have told is probably the result of an interpretation of the story of Saint Nicholas and the three innocents where, between one translation and another, the word “innocent” has been translated into “children” (pueri). The first to give this translation seems to have been Bishop Reginold in 961 after Christ, who in his treatise on the life of St. Nicholas translated “pueri” rather than “innocentes” talking about the affair of the three innocents saved by the Saint from the gallows, inspiring in the mind of the faithful a different story from the “original” that seems to be the most important among Nicholas stories, the Praxis tou agiou Nikolaou (St Nicholas’ story).

It is told that while military ships were parked in the port of Mira, the soldiers, plagued by a life of difficulties, burst into disorder in the Placoma market. This led law enforcement forces to arrest three citizens of Mira who were sentenced to death. Some citizens reached Bishop Nicholas, who was not in Mira at the time, and told him that leader Eustazio had sentenced three innocents. Nicholas hurried toward Mira but at the place called Leone came to know that the three convicts were sent to Dioscuri. Here Nicola learned that the three unlucky had already been taken to Berra, where death sentences were executed. Hurrying his march, the Saint arrived just in time, struggling through the crowd that was watching the event, to take the sword off the hand of the executioner who had already arranged the convicts on the shackles to recide their neck. After the three innocents (not “children”) have been released Nicholas went to the palace of Eustazio without being announced and accused him of corruption and violence threatening to report it to the emperor. Eustazio replied that he had been misled by two notables, Simonide and Eudossio, but Nicholas replied that it was corrupted by Crisaffio (gold) and Argiro (silver). Restoring truth and justice, Nicholas did not condemn the leader but forgave him because he repented the fact.

There is also another version, which is also the result of a “wrong” interpretation of the stories of St. Nicholas, of the legend of the “Three children and innkeeper”. This version does not speak of children but of schoolchildren. Three noble schoolchildren having to go to study in Athens, stopped at Mira to get the blessing of Bishop Nicholas. Not finding him they decided to stop at an inn for the night. The innkeeper, seeing the three well-dressed noble schoolchildren, went into their room at night, killing them, and mixing their remains with salty meat to serve it to the travelers. The following day, divinely inspired, the saint went to the inn and asked the innkeeper to show him the meat he was using as an ingredient for his dishes. The host showed the meat saying that it was great to eat and Nicola waited in the hope that the host admit the offense and repented. This did not happen, so Nicholas blessed the flesh and here the three schoolchildren returned to life. After the miracle, the innkeeper admitted his mistakes, he repented and promised to lead a virtuous life. The three schoolchildren, as they awakened by a heavy sleep, continued their journey to Athens.

There are other variants of these legends, where in some the innkeeper wife has an important and negative role, but these are the most common ones. In fact, the two legends of children and schoolchildren led to the birth of the Patronage of Saint Nicholas on children and, together with the story of the “dowry of the young ladies”, gave birth to the figure of Santa Claus (Santa Claus). In addition, from the version of the three schoolchildren, was born the patronage on schools (along with Santa Caterina d’Alessandria) and the folkloric tradition of the student festival of December 6th.

Image: Nicholas raises three children put in brine in a cask, Gentile da Fabriano, 1452 paint on wood